Changing economics move contract assembly to North America

In which direction are the economies of electronic production pushing the choice of manufacturing location? What is the history of the situation and assumptions? And when is it time to re-evaluate those assumptions?

In the 1950’s and 60’s many US and other Western companies moved manufacturing to Japan, where labor was cheap and factories were being rebuilt using enormous investments from the US and our allies. The Japanese quality was initially poor but rapidly improved and Japan became a real economic powerhouse. Along with this increased sophistication came increased cost, and western companies began the move to Korea where again, investment poured in after the Korean ceasefire.

The Koreans started out mindful of the Japanese experience and emphasized quality early on. This made Korea a better source for electronic assemblies but their smaller population (25 million Koreans vs 95 million Japanese in 1960) caused rapidly increasing labor costs. Next stop – Taiwan.

The very western-leaning government in Taipei combined with a large educated class in the workforce made Taiwan an easy fit for American companies. This writer’s personal experience working there was much like Bayonne or Bayport: the Taiwanese had a funny accent but followed the same Yankee Doodle drummer leading to escalating sophistication, profits, and cost. However by the turn of the 21st century even Taiwanese companies read the kanji on the wall and began to open subsidiaries in mainland China where land, building, and labor were cheap and often subsidized.

These lower costs coupled with the loosening governmental control in mainland China made for fertile ground where companies could expect to grow quickly and to dramatically cut costs. There was a scarcity of university-educated engineers and experienced managers, so most startups were not Chinese based but rather staffed and managed by Japanese, Koreans, and the entrepreneurial Taiwanese.

Part of the competitive nature of the Chinese model was based on low manufacturing costs, where human labor was usually more cost-effective than automation. This meant start-up capital was low but also meant that quality was more difficult to control. When output varied because of the human interface, the parts not-to-specification were simply culled out during inspection and discarded or sometimes just ignored as being “close enough”.

As the world market demanded increased quality the producers in China invested in more automation and higher caliber staff with increased training and product flow responsibility. Inevitably costs began an upward climb. The price of fuel increased globally and with it the cost to ship to their customers half-way around the globe, so the competitive nature of China began to decrease.

China has historically undervalued their currency, promoted low labor cost, and subsidized raw materials and energy costs in an effort to develop a mushrooming industrial base. This has been effective and even in the face of rising costs China’s role in the world economy has grown at the expense of other nations. There seemed to be no stopping their growth.

The international economic playing field has never been level as each country erected duties on inexpensive imports that ate away at the ability of their domestic manufacturers to grow and develop. A second tool used to give home-grown industries a boost has been subsidies (often farm products) and government sweetheart contracts (the aerospace industry). Any effort by an industrialized country to harmonize trade with developing countries has received resistance and threats of suits in international courts. The “balance of trade” has been a key measurement, contrasting imports from and exports to specific trading partners. However even when the numbers pointed to a disparity there was little a country could do to level the playing field. Then came the tariffs.

Tariffs are a double-edged sword, protecting targeted industries while adding to the cost of living for the population in general. The goal is usually to make them last long enough to spur domestic protection and short enough to avoid a dramatic increase in the cost of living or an outright shortage of certain goods.

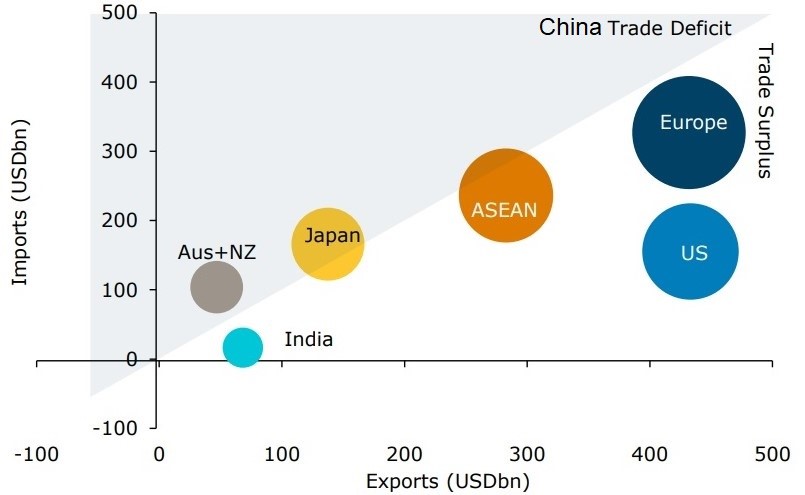

China’s largest export market is the US, and they export to the US five times the amount that they import from the US. The Chinese trade with the EU is more balanced but still far in Chinese favor.

The Chinese economic growth plan is based on maintaining and even increasing this advantage, but that could hold true only if their trading partners were willing to accept the status quo at the expense of their domestic industries. Tariffs are one way to force a short-term rectification of the imbalance.

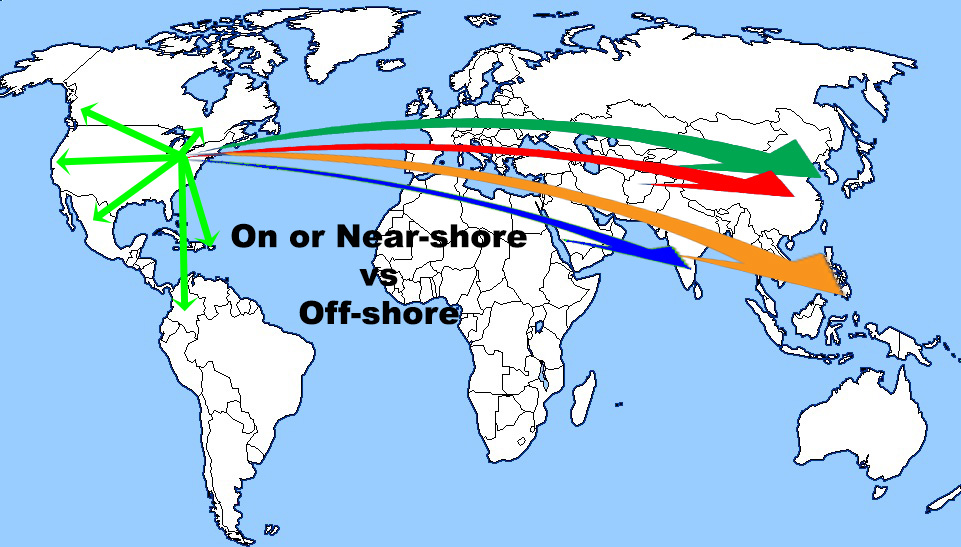

The US has imposed punitive tariffs on a wide range of raw materials and finished goods from simple metal extrusions to sophisticated electronics. Ten per cent has grown to 25%, and $50 billion in goods to $300 billion in goods, nearly every product imported. The short-term effect is already being seen with American companies sourcing to other low-cost regions or moving production back to the US. As China struggles with lower output their cost to produce is rising, reducing their cost advantage against other countries. Headlines are already reporting that China may have missed its opportunity to grow into an economic giant. Bad for them does not necessarily mean good for us, but it does mean that American companies have decisions to make in the next few years. Electronics assembly production is a prime example of an industry in transition. Will we go to other LCR and repeat this scenario or will we re-shore?

The North American sources for contract assembly, having watched their markets shrinking away, are seeing a ray of hope: they could compete on the world stage and indeed win the economic struggle not only against the historical competitors but also against any of the new smaller (Vietnam, Thailand) and potentially larger (Brazil, India) low cost regions.

Let us review the actual history and trends in China, realize what has happened to the cost savings that were envisioned just a few years ago, and take heed

The Supporting Data:

Seven years ago the push to offshore contract assembly was at its peak, and with good reason. US demand was up and volumes were increasing. US labor and raw material costs had risen dramatically. Cheap knockoffs from Chinese companies were flooding the market. To compete the US companies chose to join them, not fight them, and began moving first simple subassemblies and then more complete products to LCRs (low cost regions) like China and Vietnam.

We, the American consumer, cannot blame the US off-shoring companies. We wanted more and we wanted it cheaper. We accepted lower quality because ours was a throw-away society – use it for a while and when it breaks just buy a cheap replacement. We went from buying just the most basic components off-shore to buying completed goods, all made in the world’s LCR.

Today however that tide is turning. The change in currency exchange alone has made this a different world. The US dollars just do not buy as much off-shore as it used to.

The environmental mantra of “reduce, reuse, recycle” has taken hold. Americans are willing to pay a bit more for things of a higher quality that might last longer. Would we pay double? Probably not. So where is that tipping point and how close to it are we? When should producers in this hemisphere investigate on-shore contract assembly? Let’s look first at recent changes in cost in the Pacific Rim.

- Chinese labor costs have doubled and are expected to rise another 50% in 4-5 years.

- Chinese currency is more expensive: it had been over 8¥/$, and is now <7¥/$.

- The cost of shipping products has increased, some rates by 43%, others by more.

If you left our shores for contract assembly in the Far East, and you then saved one-half of your production cost, how much of that savings remains today? 15%? 10%? Less??? Even just 10% might be a reason to let the business remain there because after all, why incur an avoidable cost increase? Are there issues that must be considered in addition? The answers might be in the less obvious areas.

Doing business around the world has obvious hurdles, like language. There are also less obvious obstacles like business mindset and ethics. We in the West have standards that differ even on a single continent. We should not be surprised to discover that there is a greater difference between cultures with less history in common. That is not to say that one is better than the other, only that they are different and must be taken into account in negotiations and daily business transactions.

What are other practical issues that impact an OEM’s business when considering off-vs-on shoring?

- Should you invest in an overseas (Vietnam, India, Singapore) manufacturing scenario today if there are major aspects over which you have limited control, and there are forecasts of increasing economic pressure?

- The 10 to 12 hour time difference: how easy is it to have a phone or video conference if one group is just arising while the other is getting ready for dinner? Is everyone really at the top of his game?

- The 24 hour trip to have an on-site round table discussion. How many of your staff could you spare at the same time so as to make the meeting truly productive? And what happens back home while they are gone – it is still that 12 hour phone tag lag.

- What is the background, ability, and availability of the LCR staff? Do they have the skillset that you are used to encountering? Do they smile and nod because they agree or because they do not understand?

- Are your quality standards something that they are just willing to accept or do they wholeheartedly embrace the concept? Are they committed to protect the product quality and hence the good name of their clients or would they walk away from a situation and just move on to another client from a different industry or different country. After all, their name is shielded from notoriety by secrecy agreements.

- And speaking of secrecy, how is your intellectual property protected? Agreements for non-disclosure are easy to sign but difficult to enforce when the parties are separated by 8,000 miles, different legal systems, and centuries of tradition.

Quantifying these non-monetary aspects is difficult but we know they exist. When do they, added to the direct cost, warrant moving your contract assembly back to North America?

This question could be answered with the use of a super computer and the services of many an expensive consultant. Or you could bid your next job here and there, compare the economic results, factor in the ease of dealing locally, and make your first on-shore placement. You will not be the first in North America to make that change and you will certainly not be the last. If you would like a helping hand as you make your decision, just ask USTEK Incorporated – we have the experience!

Comments are closed